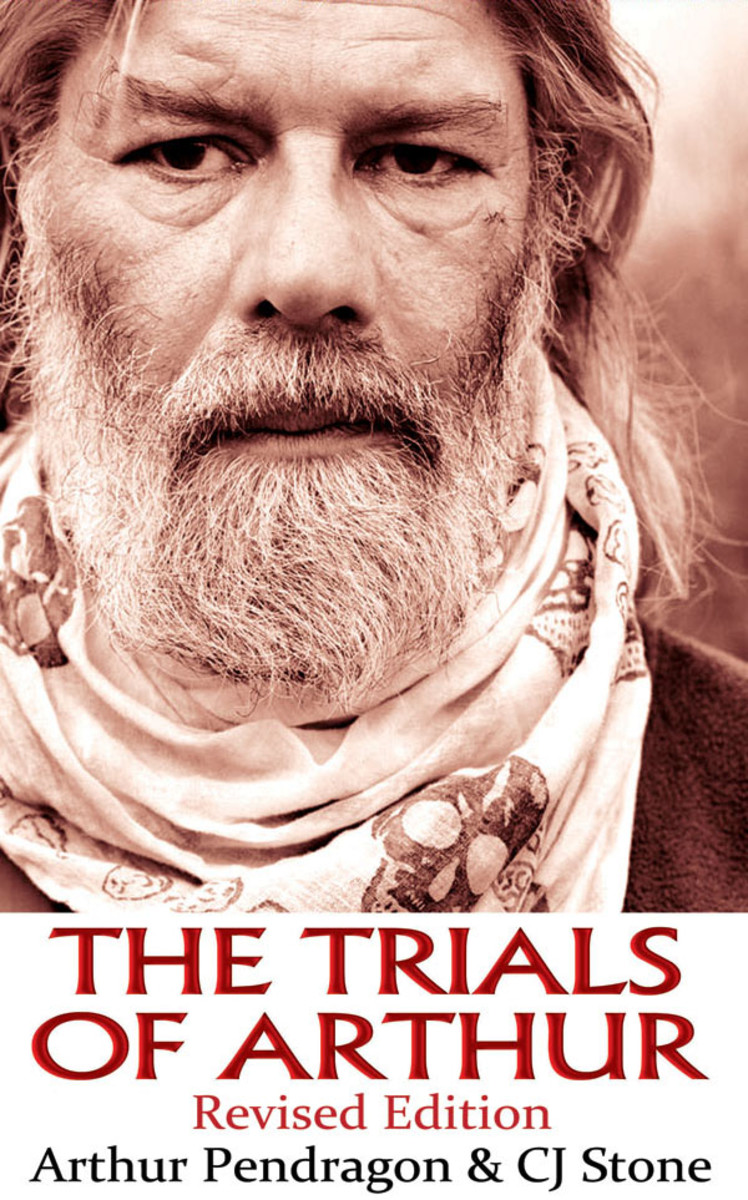

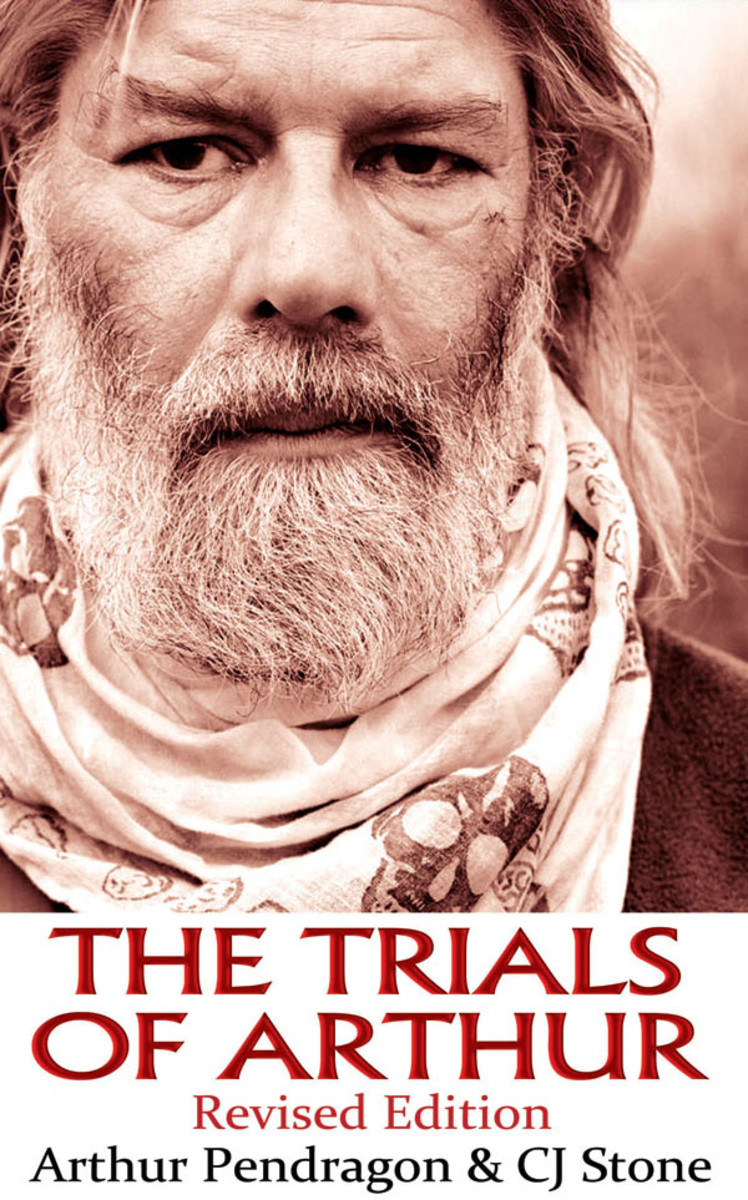

Being an unused chapter from The Trials of Arthur Revised Edition

Being an unused chapter from The Trials of Arthur Revised Edition

King Arthur

In 1996 I went looking for King Arthur.

Not the historical Arthur, you understand. No, a modern day Arthur: a biker, a druid and an eco-warrior, living here in the UK, who was making a name for himself at the time by going around calling himself King Arthur.

I wanted to write a book about him.

I spent the better part of the year on my quest to find him. I was driving from my home town in Kent, the county of the Saxons, westwards into the Celtic lands, to the two great Stone circles at Avebury and Stonehenge, and to Glastonbury in Somerset, following the A303, always with some specific instruction to meet him at such and such a place, at such and such a time, usually passed on to me by Steve Andrews, the friend who had originally told me about Arthur, and every time I got to wherever it was, he wouldn’t be there. Something would have happened to hold him up. Or he just went somewhere else instead. We were like two satellites whirling about in the night sky on two separate orbits, skimming quite close to each other at times, but never quite meeting.

I got to go to a lot of druid ceremonies in this time. I stood around in circles in fields in the early morning while the mists were rising, listening to incantations and chants and mysterious-sounding prayers. I watched as people did things with flowers and goblets of mead and bits of bread and knives and swords. I said, “hail!” to this and “hail!” to that. I watched as people divided the circle into quarters and summoned up the spirits of the four directions. I said “Hail,” to the East, and “Whatcha” to the South, and “Hiya,” to the West and “Howdy” to the North. I listened as people likened the four quarters to the four elements. The East was Air, the South was Fire, the West was Water, the North was Earth. I joined in as we did the “I-A-O” as a long-drawn-out chant, the vowel sounds blending into each other, and travelling around the circle with a life of their own. The chant would rise and fall around the circle, lift into the air a little, like a spacecraft about to take off, before falling into silence again. I didn’t know what any of it was for really. It felt like I was in Church, only someone had forgot to put the heating on. Or the roof, come to that. It was often very cold.

You may wonder why I was doing this? Why was I going to all this trouble? Whenever I described my quest to anybody, the response was almost immediate. “He thinks he’s King Arthur you say? So where are you meeting him then? In a lunatic asylum?”

I was doing it all on the say-so of my friend Steve, who was – is — by his own admission, something of an eccentric.

Steve believes in all sorts of things that other people don’t believe in. He believes in the presence of ETs amongst us. He believes that a vast, all encompassing alien conspiracy is overwhelming our world. He believes in gods and demons and angels and aliens, and crop circles and hidden technologies and great forces at work on our planet. He used to be a scientologist. He’s tried every kind of belief system you can imagine. He’s been on a quest all his life, to find out the truth behind the appearance of things. He has a taste for the unusual and the arcane and lists amongst his friends people who think they are aliens, people who think they are gods, and people who think they are gurus.

So why not a person who thinks he’s King Arthur too? Maybe King Arthur is just another one of these weird people that Steve has a taste for. But, then, maybe that doesn’t matter either.

Myth

One of the words we sometimes use for a particular category of belief is “myth”. Myths are the stories we tell ourselves. Sometimes we use the word to mean something that is demonstrably untrue. Sometimes we use the word to mean a fiction. However, sometimes fiction can convey more truth than the facts, as in the great works of art. Shakespeare wasn’t writing the truth in the literal sense. His plays are all fictions. But they contain greater truths than the facts could convey. Mythic truths. Truths which speak to the heart.

This is the sense in which I am using the word “myth”, to describe the great works of art and the structures of thought of a civilisation, as in “the Greek Myths”. The “myths” here are not false in the sense that they are delusions. They are the mental and emotional map of the landscape of the mind of a people. The gods and the demigods, the satyrs and the fauns, the nymphs and the muses, Fates and gorgons, centaurs and heroes, Zeus and Artemis, Dionysus and Ares, are the psychic inhabitants of the ancient Greek’s inner country. They are their own description of the forces that worked upon their world, told in the form of stories. They represent the accumulated experience of the Greek people over many thousands of years.

Our modern world, too, is the product of a myth. It’s a myth that is so all-pervasive, so present, so all-encompassing, that we don’t even know it is there. It has shaped our world. The stories we used to tell, about gods and demons and heroes and divinities, battling it out in a cosmic scale to create the world, have given way to another myth. There are no gods or demons any more. There are market forces instead. The new myth is money, and like the old myth, it too has its gurus and its theologians and its priests and its bishops, its oracles and its soothsayers, its protesters and its poets. It too has its superstitions and its stories. Market traders pray to their own private gods. In this way the new myth and the old myth intertwine. And out of this myth our world is fashioned. And where a motorway is carved, or a wood is destroyed, or a new shopping complex is built where once animals nested, is determined by this myth. Why we get up in the morning and what we do with our day. Our rituals and our habits. The layout of our houses. The technology we use. Everything is laid down in the loom of the myth in a certain pre-determined pattern. We’ve grown so used to it, we’ve forgotten it is there. We just view it as our daily life. We make choices within the myth. We decide what colour our wallpaper will be, what shops to go to and what to watch on TV that night, but we’ve forgotten that there might be choices outside of the myth. We’ve forgotten that there might be other myths to choose from.

This is where Arthur comes in. King Arthur is a myth. He is a set of stories laid down by history. He represents the history of a people, an accumulation of themes, a chapbook of memories, a guide to action. Was there ever a “real” King Arthur or not? It doesn’t matter. In the country of the mind everything is real.

So there are a set of old stories in the ancient Celtic tongue, about a hero who fought the Saxons, a warrior Arthur, who may have led a band of knights in that Dark Ages period after the Romans had left: fast moving cavalry men, trained in the art of battle, who raced about the country, from Caledonia to Cymru, holding back the Saxon hoards in their invasion of this ancient land. This may or may not have happened. One of the stories tells us that he was a Christian warrior who carried a cross on his shoulders and by that means defeated his enemies, another that he carried an image of the Virgin Mary. He is rarely described as a King. Sometimes he is called “the soldier Arthur,” sometimes “the tyrant”.

Whatever: it is a very different Arthur we meet in these ancient tales than the one we meet in the medieval stories. He is more robust, more flawed, more mysterious, in a sense more real, than the courtly Arthur of the later romances.

Three Powerful Swineherds of the Island of Britain:

One particular story tells of a pig-rustling episode. This is from the Welsh Triads, a set of mnemonics designed to give the outline of a story for a poet to embellish. The Triads were written down in Medieval times but obviously refer to a more ancient tradition of oral poetry. The story is called The Three Powerful Swineherds of the Island of Britain, and it does just that, it tells you the names of the three swineherds: Pryderi son of Pwyll, Drystan son of Tallwch and Coll son of Collfrewy. It also tells you who they were keeping the swine for, and where: in what particular field, in what town and what county. The story is rural and parochial rather than courtly and elevated. It’s a completely different kind of story than the ones told by Chrietien de Troyes or Malory in later centuries.

Arthur and March and Cai and Bedwyr are in this story, names we recognise from the romances, only they are attempting to steal pigs. They try force at first, but fail. We are left to imagine what kind of force. Did they undertake a full-scale assault on the pig-run? It’s not exactly the Holy Grail is it? It’s not quite a knightly quest. They are fighting for pigs rather than maidens. Their purpose is earthly rather than spiritual. Later, force having failed, they try deception. Again they fail. You wonder what the deception might be? Perhaps they posed as buyers, or tried to trick the swineherds of their pigs. Perhaps they got the swineherds drunk and tried to beat them at dice. Finally they try stealth, creeping up on the pig-run late at night, under the cover of darkness. Again they fail.

Where is the Chivalrous Arthur here? Where are the Maidens, the Jousts, the Quests? Arthur wants to steal some pigs and he uses every kind of underhand trick to get them.

And then a strange magical element is brought into the story. Coll son of Collfrewy, is tending the swine of Dallwyr Dallben in Glyn Dallwyr in Cornwall. One of the swine is pregnant. We are given her name. It is Henwen. And there is a prophecy attached to this pregnancy, “that the Island of Britain would be the worse for the womb-burden.” How could this be? How could the pregnancy of a pig affect the fate of a nation? We’re obviously into some mythic territory here.

Arthur raises an army in order to destroy the pig. There is a chase: a pig-chase. Henwen is about to give birth and is looking for a place to nest. You wonder what kind of an army this is, to spend its time chasing pregnant pigs?

At Penrhyn Awstin in Cornwall the pig enters the sea, with the powerful swineherd close on her heels. We presume the powerful swineherd is Arthur, although it’s not made explicit. Then she enters a wheat field in Gwent and gives birth to a grain of wheat and a bee. “And therefore from that day to this the Wheat Field in Gwent is the best place for wheat and for bees.” Then she goes to Llonion in Pembroke where she gives birth to a grain of barley and a grain of wheat. “Therefore, the barley of Llonion is proverbial.”

Creation

She is clearly not any old pig any more. She is a totem animal giving birth to the world and to the primal forces within it. Some of it is fruitful, but some of it is not. At the Hill of Cyferthwch in Arfon she gives birth to a wolf-cub and a young eagle. “The wolf was given to Mergaed and the eagle to Breat, a prince of the North: and they were both the worse for them.” They are animals of ill-omen. Wolves and eagles are the enemies of man-kind. They attack the domesticated herds of the human landscape. The wilderness is encroaching upon the homestead. Arthur and his army have chased the birth-pig to the edges of the wilderness, where the wild creatures reign. The creatures are given to princes of the realm but bring them bad luck. In the heart of the civilised world, the wilderness still casts its dark spell.

Finally, at Llanfair in Arfon, Henwen the magical pig of creation, gives birth to a kitten. The place of birth is described: under the Black Rock. The Powerful Swineherd takes decisive action: he throws the kitten from the Rock and into the sea. But the kitten does not die. Instead the sons of Palug take care of it in a place called Môn. Like the eagle and the wolf before it, it brings only harm. “That was Palug’s Cat, and it was one of the Three Great Oppressions of Môn, nurtured therein. The second was Daronwy, and the third was Edwin, king of Lloegr.”

We don’t know what kind of harm Palug’s Cat causes. We don’t know what the Three Great Oppressions of Môn are, or who these other people are. This is a mnemonic not a story. It gives the elements of the story in their proper order, but the poet is supposed to know the details off by heart, and to be able to recite them in a poem. Thus we are given no more clues than this.

The story is both rustic and magical at the same time. It is local, and it is universal. We have hints of a more ancient Arthur here: a pre-Christian Arthur. The great Quests of the Medieval Romance are preceded by a pig-chase. The mystical concept of the Holy Grail is a substitute for a pig in labour. But like the Wasteland that is associated with the Grail Quest, the pig is ill-omened, and gives birth to a blight upon land.

What kind of a landscape are we entering? And who is this Arthur, suddenly transformed into a Powerful Swineherd who sacrifices kittens by throwing them into the sea? It’s no easy story this. Blights and blessings harrowed from the womb in convulsive birth. Vast armies raised to chase magical pigs. Hints of treachery and sacrifice and a list of names that cleave the tongue to the palate, so specific and precise in their references that they seem to be based on real people. And if these swineherds and their pigs are real, why not Arthur too? Why not March and Cai and Bedwyr?

We’re caught between two worlds here: between the mundane and the magical, the natural and the supernatural. The landscape seems real. The places are real. The people bear names that make it sound as if they are characters from history. But the divine pig, Henwen, traverses this landscape giving birth to the elements along the way. It is small scale and large scale. It is past and present. It is the landscape of rural Britain– contemporary when the story was first spoken – of small farms and homesteads, in which a magical act of creation is taking place at the origins of the world itself.

And that, too, is the nature of our story: a 21st century legend set amongst the motorways and housing estates, the shopping centres and factories of the modern world, but in a place where the myth is real, where creation has its being, and where a magical act of transformation can change the world.

Read more about the book:

- The Trials of Arthur

Free sample chapter from The Trials of Arthur. Chapter 17: Camelot (Of Cabbages and Kings) - The Wild Hunt: Guest Post

The following is a guest post from CJ Stone on the newly revised Kindle edition of his book, “The Trials of Arthur,” which explores the life and work of British Druid activist Arthur Pendragon - CJ Stone: Why I (re)wrote The Trials Of Arthur; The Big Hand

I wrote the original version of The Trials of Arthur between 2000 and 2003. It was a book I’d wanted to write for a long time. I’d originally come across Arthur Pendragon in the mid-nineties, through my good friend Steve Andrews… - Trials of Arthur facebook page

Links, reviews, articles, videos about Arthur Pendragon & The Trials of Arthur. - Is Arthur Pendragon the Reincarnation Of King Arthur?

King Arthur is this ex-biker, ex-soldier, ex-builder who had a brainstorm back in the eighties and decided he was King Arthur, after which he donned a white frock and a circlet, and has been causing various kinds of trouble ever since. - The Trials of Arthur Revised Edition reviewed for HubPages

Just about everybody has heard of the legend of King Arthur and his Knights of the Round Table but perhaps you are not aware that there is a man around today who calls himself King Arthur Uther Pendragon and believes he is the reincarnation - CJ Stone interview; The Big Hand

The Trials of Arthur tells the story of how a biker and ex-squaddie decided that he was King Arthur and that his quest was to free Stonehenge from the government’s exclusion zone. This he eventually achieved – after first finding Excalibur… - Synchronicity: the Magic of Imagination

Synchronicity is not external to us, it is internal to us. It is not a law of nature, it is a choice we make. Does the universe have meaning? Yes it does. It has the meaning we choose to give it. - Amazon.co.uk: Customer Reviews: The Trials of Arthur: Revised Edition

Imagination

Imagination